The Past, Present & Future of Local Storage for Web Applications

Persistent local storage is one of the areas where native client applications have held an advantage over web applications. For native applications, the operating system typically provides an abstraction layer for storing and retrieving application-specific data like preferences or runtime state. These values may be stored in the registry, INI files, XML files, or some other place according to platform convention. If your native client application needs local storage beyond key/value pairs, you can embed your own database, invent your own file format, or any number of other solutions.

Historically, web applications have had none of these luxuries. Cookies were invented early in the web’s history, and indeed they can be used for persistent local storage of small amounts of data. But they have three potentially dealbreaking downsides:

- Cookies are included with every HTTP request, thereby slowing down your web application by needlessly transmitting the same data over and over

- Cookies are included with every HTTP request, thereby sending data unencrypted over the internet (unless your entire web application is served over SSL)

- Cookies are limited to about 4 KB of data — enough to slow down your application (see above), but not enough to be terribly useful

What we really want is

- a lot of storage space

- on the client

- that persists beyond a page refresh

- and isn’t transmitted to the server

A Brief History of Local Storage Hacks Before HTML5

In the early there was only Internet Explorer that we are used a lot . Microsoft wanted let the world to think. To thet end , as a part of the First Great Browser Wars, Microsoft invented a great lot of things and incloded them in their browser-to-end-all-browser-wars, Internet Explorer. One of these things was called DHTML Behaviors, and one of these behaviors was called userData.

userData allows web pages to store up to 64 KB of data per domain, in a hierarchical XML-based structure. (Trusted domains, such as intranet sites, can store 10 times that amount. And hey, 640 KB ought to be enough for anybody.) IE does not present any form of permissions dialog, and there is no allowance for increasing the amount of storage available

In 2002, Adobe introduced a feature in Flash 6 that gained the unfortunate and misleading name of “Flash cookies.” Within the Flash environment, the feature is properly known as Local Shared Objects. Briefly, it allows Flash objects to store up to 100 KB of data per domain. Brad Neuberg developed an early prototype of a Flash-to-JavaScript bridge called AMASS (AJAX Massive Storage System), but it was limited by some of Flash’s design quirks. By 2006, with the advent of ExternalInterface in Flash 8, accessing LSOs from JavaScript became an order of magnitude easier and faster. Brad rewrote AMASS and integrated it into the popular Dojo Toolkit under the moniker dojox.storage. Flash gives each domain 100 KB of storage “for free.” Beyond that, it prompts the user for each order of magnitude increase in data storage (1 Mb, 10 Mb, and so on).

In 2007, Google launched Gears, an open source browser plugin aimed at providing additional capabilities in browsers. (We’ve previously discussed Gears in the context of providing a geolocation API in Internet Explorer.) Gears provides an API to an embedded SQL database based on SQLite. After obtaining permission from the user once, Gears can store unlimited amounts of data per domain in SQL database tables.

In the meantime, Brad Neuberg and others continued to hack away on dojox.storage to provide a unified interface to all these different plugins and APIs. By 2009, dojox.storage could auto-detect (and provide a unified interface on top of) Adobe Flash, Gears, Adobe AIR, and an early prototype of HTML5 storage that was only implemented in older versions of Firefox.

As you survey these solutions, a pattern emerges: all of them are either specific to a single browser, or reliant on a third-party plugin. Despite heroic efforts to paper over the differences (in dojox.storage), they all expose radically different interfaces, have different storage limitations, and present different user experiences. So this is the problem that HTML5 set out to solve: to provide a standardized API, implemented natively and consistently in multiple browsers, without having to rely on third-party plugins.

Introducing HTML5 Storage

What I will refer to as “HTML5 Storage” is a specification named Web Storage, which was at one time part of the HTML5 specification proper, but was split out into its own specification for uninteresting political reasons. Certain browser vendors also refer to it as “Local Storage” or “DOM Storage.” The naming situation is made even more complicated by some related, similarly-named, emerging standards that I’ll discuss later in this chapter.

So what is HTML5 Storage?

Simply put, it’s a way for web pages to store named key/value pairs locally, within the client web browser. Like cookies, this data persists even after you navigate away from the web site, close your browser tab, exit your browser, or what have you. Unlike cookies, this data is never transmitted to the remote web server (unless you go out of your way to send it manually). Unlike all previous attempts at providing persistent local storage, it is implemented natively in web browsers, so it is available even when third-party browser plugins are not.

Which browsers? Well, the latest version of pretty much every browser supports HTML5 Storage… even Internet Explorer!

HTML5 Storage support

|Browsers|Storage| |——–|——-| |IE |8.0+ | |Firefox |3.5+ | |Safari |4.0+ | |Chrome |4.0+ | |Opera |10.5+ | |iPhone |2.0+ | |Android |2.0+ |

From your JavaScript code, you’ll access HTML5 Storage through the localStorage object on the global window object. Before you can use it, you should detect whether the browser supports it.

check for HTML5 Storage

function supports_html5_storage() { try { return 'localStorage' in window && window['localStorage'] !== null;} catch (e) { return false; }}

- Instead of writing this function yourself, you can use Modernizr to detect support for HTML5 Storage

if (Modernizr.localstorage) {// window.localStorage is available!} else {// no native support for HTML5 storage :(// maybe try dojox.storage or a third-party solution}

Using HTML5 Storage

HTML5 Storage is based on named key/value pairs. You store data based on a named key, then you can retrieve that data with the same key. The named key is a string. The data can be any type supported by JavaScript, including strings, Booleans, integers, or floats. However, the data is actually stored as a string. If you are storing and retrieving anything other than strings, you will need to use functions like parseInt() or parseFloat() to coerce your retrieved data into the expected JavaScript datatype.

Tracking Changes to the HTML5 Storage Area

If you want to keep track programmatically of when the storage area changes, you can trap the storage event. The storage event is fired on the window object whenever setItem(), removeItem(), or clear() is called and actually changes something. For example, if you set an item to its existing value or call clear() when there are no named keys, the storage event will not fire, because nothing actually changed in the storage area.The storage event is supported everywhere the localStorage object is supported, which includes Internet Explorer 8. IE 8 does not support the W3C standard addEventListener (although that will finally be added in IE 9). Therefore, to hook the storage event, you’ll need to check which event mechanism the browser supports. (If you’ve done this before with other events, you can skip to the end of this section. Trapping the storage event works the same as every other event you’ve ever trapped. If you prefer to use jQuery or some other JavaScript library to register your event handlers, you can do that with the storage event, too.)

Storage Event Object

|Property|Type|Description | |——–|——-|—————-| |key |string |the named key that was added, removed, or modified | |oldValue| any |the previous value (now overwritten), or null if a new item was added | |newValue | any | the new value, or null if an item was removed | |url* |string | the page which called a method that triggered this change |

- Note: the url property was originally called uri. Some browsers shipped with that property before the specification changed. For maximum compatibility, you should check whether the url property exists, and if not, check for the uri property instead.

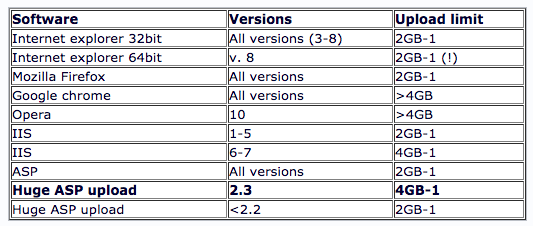

Limitations in Current Browsers

In talking about the history of local storage hacks using third-party plugins, I made a point of mentioning the limitations of each technique, such as storage limits. I just realized that I haven’t mentioned anything about the limitations of the now-standardized HTML5 Storage. I’ll give you the answers first, then explain them. The answers, in order of importance, are “5 megabytes,” “QUOTA_EXCEEDED_ERR,” and “no.”

Beyond Named Key-Value Pairs: Competing Visions

While the past is littered with hacks and workarounds, the present condition of HTML5 Storage is surprisingly rosy. A new API has been standardized and implemented across all major browsers, platforms, and devices. As a web developer, that’s just not something you see every day, is it? But there is more to life than “5 megabytes of named key/value pairs,” and the future of persistent local storage is… how shall I put it… well, there are competing visions.

Further Reading